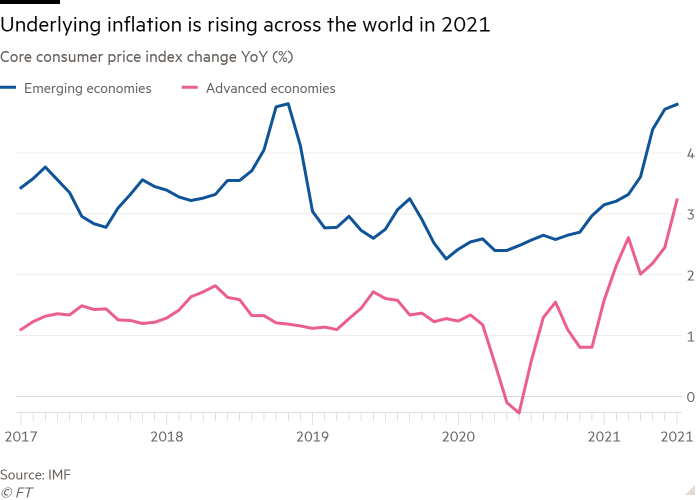

The global economy is entering a phase of inflationary risk, the IMF warned on Tuesday, as it called on central banks to be “very, very vigilant” and take early action to tighten monetary policy should price pressures prove persistent.

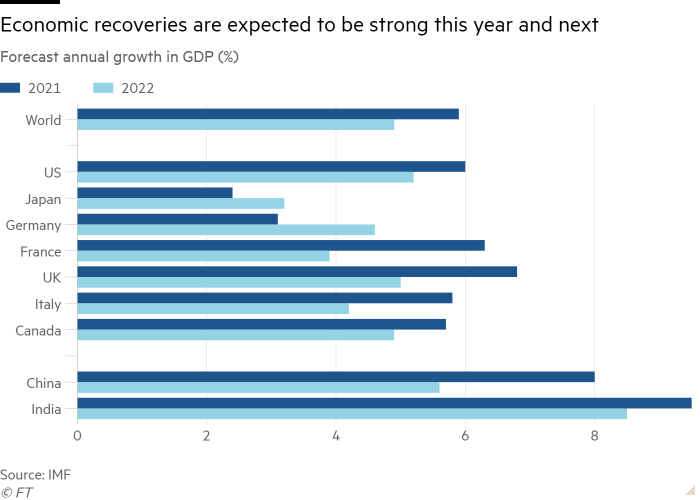

The fund was highlighting the new risks in its twice-yearly World Economic Outlook, which also warned of slipping momentum in global growth after a strong recovery so far this year.

Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s chief economist, said the strength of the economic recovery meant it was too early to “say anything about stagflation”, despite some supply shortages which have also boosted inflation.

“We always knew coming out of this deep contraction that the supply-demand mismatch would pose problems,” she told the Financial Times.

“The hope was that it would even itself out by around this time of the year . . . But we’ve been hit with additional shocks, including some weather-related shocks, that certainly makes that imbalance persist longer,” Gopinath said.

The IMF’s central forecast is that inflation will rise sharply towards the end of the year, moderate in mid-2022 and then fall back to pre-pandemic levels. But its report also noted that “inflation risks are skewed to the upside” and advised central banks to act if price pressures showed signs of lasting.

The fund said central banks should generally ignore higher prices that stemmed from energy price shocks or temporary difficulties in bringing products to market. But it should act if there are signs that companies, households or workers start to expect high inflation to linger.

“What [central banks] have to watch out for is the second-round effects [with] these increases in energy prices feeding into wages and then feeding into core prices. That’s where you have to be very, very vigilant,” Gopinath said.

The report was clear that “central banks . . . should be prepared to act quickly if the recovery strengthens faster than expected or risks of rising inflation expectations become tangible”.

That meant getting ahead of the curve on prices even if employment is still weak, the IMF recommended, as that is preferable to allowing inflationary mindsets to become ingrained.

“A spiral of doubt could hold back private investment and lead to precisely the slower employment recovery central banks seek to avoid when holding off on policy tightening,” the IMF warned.

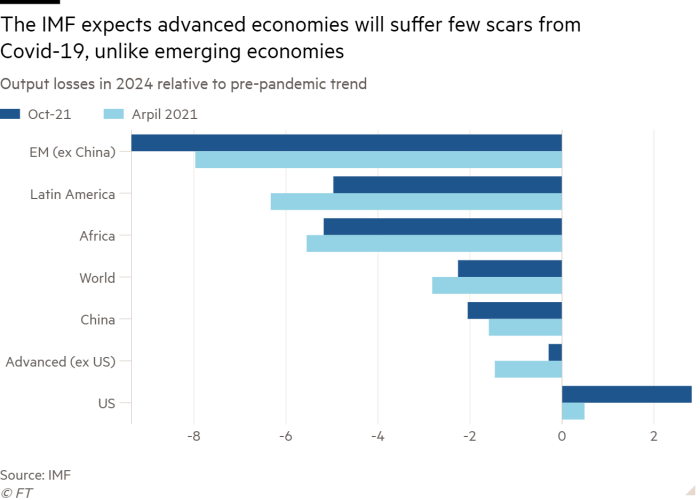

If central banks successfully navigate the inflation risks ahead, the fund expects advanced economies to recover fully from the pandemic, returning to the path that they were on before coronavirus struck.

Defending the integrity of IMF forecasts following the manipulation of the World Bank’s Doing Business rankings when Kristalina Georgieva, now the head of the fund, was its chief executive, Gopinath said the World Bank’s difficulties “have nothing to do with the IMF”.

“We have an incredibly robust and thorough review process of our data and our forecasts, where we have multiple economists in multiple departments who review it and provide detailed comments.”

The funds’ forecasts were little changed from those in April. The IMF expects the global economy to grow 5.9 per cent in 2021, decreasing to 4.9 per cent next year.

Inflation in advanced economies is expected to average 2.8 per cent this year, and then fall to 2.3 per cent in 2022. However, these inflation forecasts were revised up by 1.2 percentage points and 0.6 percentage points respectively from April, indicating the scale of the new inflation threat.

The IMF also noted that even when the pandemic is over, emerging economies and low-income countries would be hit much harder in the long term.

Not including China’s, they are likely in 2024 to be almost 10 per cent smaller than expected before the pandemic struck.