When Giancarlo Devasini first got into cryptocurrencies in 2012, his interests were distinctly small-time. He piped up on a popular Bitcoin forum to ask if anyone wanted to buy DVDs or CDs for 0.01 bitcoin each, then roughly 11 cents, promising free shipping for bulk orders.

Today, the 57-year-old is one of the most influential players in the global cryptocurrency marketplace. From his position as chief financial officer at Bitfinex, a major exchange, and at Tether, its sister currency which has tokens worth $60bn in circulation, industry executives say that he is the key decision maker at two companies that now sit at the heart of the opaque daily flows of crypto money worth billions of dollars.

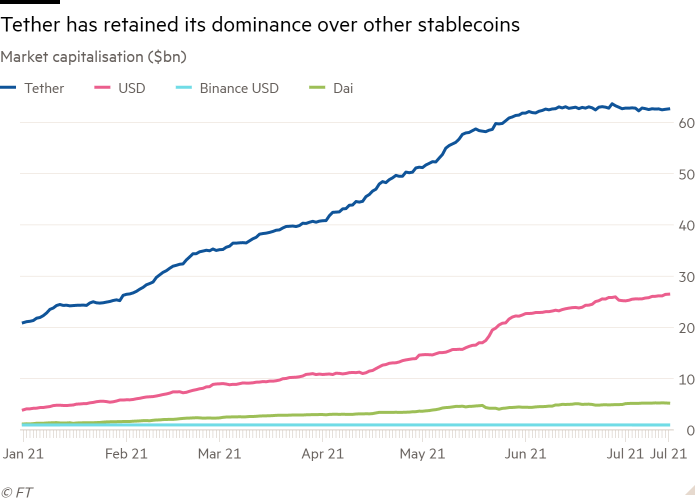

As the world’s largest “stablecoin”, meaning a cryptocurrency pegged to other assets, Tether is an indispensable lubricant for investors moving in and out of more volatile cryptocurrencies. As a result of its dollar-asset backing, it has become the de facto reserve currency of the global crypto economy.

Tether is also deeply controversial, with government authorities warning about the possible risks it poses to broader markets and questioning past statements it has made about the assets behind the currency.

Earlier this year, the New York attorney-general, Letitia James, said Tether had lied in the past about its reserves and called Devasini and his colleagues “unlicensed and unregulated individuals . . . dealing in the darkest corners of the financial system”. The companies say those phrases were not in the $18.5m settlement struck with the attorney-general’s office announced in February.

Last month, Eric Rosengren, the president of Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, named Tether as a possible challenge to financial stability, saying: “In effect, this is a very risky prime fund.” Prime funds invest primarily in corporate debt and allow investors to withdraw cash at will.

The significance of the cryptocurrency is hard to overstate: currently around half of all bitcoin trades are transacted using Tether, according to Crypto Compare, helping to propel the dramatic rise in bitcoin’s price this year. Tether has given crypto-traders a dollar-like token of exchange, without the hassle and risks of using real dollars.

At the centre of the two ventures is Devasini. Though formally junior to his longtime business partner, Tether and Bitfinex chief executive Jean-Louis van der Velde, Devasini is seen as the central figure by some in the market.

“The guy who runs it is Giancarlo,” says a crypto company executive. Devasini himself boasted in an audio chatroom in 2016: “At the end, I am the guy that calls the shots in Bitfinex.” Tether says Devasini and van der Velde both play “vital roles at Bitfinex and Tether based on their individual experiences and expertise”.

Devasini’s status as a titan of crypto finance, playing a central role in the vast sums of speculative money flowing into cryptocurrencies, is a remarkable transformation from his previous careers in plastic surgery, trading computer hardware and building a healthy-eating food delivery service.

Moulding a career

He was born in Turin in 1964 and trained as a doctor at the University of Milan. His first calling was as a plastic surgeon, although he quit the profession just two years out of university in 1992 after despairing at the job.

“All my work seemed like a scam, the exploitation of a whim,” he told an Italian art gallery in 2014. He recounted his particular frustration that one woman could not be talked out of reducing her breasts even though they “fit her perfectly”, as he put it.

Tether says Devasini had not himself performed that particular procedure and that he had been concerned the woman would be disappointed with the results.

The young doctor turned away from moulding flesh and embarked on a career dealing in electronics. He built a group of companies in Italy that, according to his Bitfinex profile page, and reiterated by Tether in response to questions from the FT, he grew to over €100m in revenue and which he says he sold shortly before the 2008 financial crisis.

Italian company documents cast his business background in a very different light. In 2007, Devasini’s business empire had revenues of just €12m and was subsequently dealt a deathblow by a devastating fire at Devasini’s warehouse and offices in February 2008. The parent company of the group, Solo, went into liquidation in June that year. The subsidiaries, Acme, Compass and Freshbit, had been written down to a nominal €1 value apiece in Solo’s 2007 accounts. Tether insists that Devasani “portrayed the facts entirely accurately”.

At some point during his almost two decades selling computer hardware, Devasini adopted the alias “Merlin” in many of his communications and the Skype handle “merlinmagoo”. One associate in 2010 referred to him as “Mr Merlin”.

Like the mythological wizard, Devasini had his share of scrapes.

In 1996, not long after he had left medicine for business, he paid 100m lira — then around $65,000 — in a counterfeiting settlement with Microsoft. A decade later, in 2007, Toshiba sued another of his entities, Acme, for alleged infringement of its patents for DVD format specifications.

Tether says Devasini had unwittingly loaded unlicensed Microsoft software on to computers he was selling after relying on the assurances of a supplier and that he had co-operated with the authorities investigating the matter. They added the Toshiba lawsuit had been “meritless”, “went nowhere” and “resulted in no adverse finding”.

In 2006, one of his companies, Alcosto, bought 1,575 memory chips from a UK business. A UK tax tribunal in 2016, in a case not involving Devasini, found that the transaction was one of several “linked to fraudulent tax losses” as part of a missing-trader scheme.

Such schemes involve long chains of trades, which may include unsuspecting businesses, where the final buyer claims a refund for value added tax from the government but the original seller, who is liable to the government for the same amount, disappears.

“The only ‘fraudulent tax losses’ we’re aware of were the result of a failure of one of Alcosto’s customers to pay taxes — not Alcosto itself,” says Tether.

In March 2010, another of Devasini’s companies, a Monaco entity called Perpetual Action Group, was banned from Tradeloop, the online used-electronics marketplace. A month earlier, an American buyer had complained about $2,000 worth of memory chips they had bought from PAG. “[One] box was filled with a large block of wood,” the buyer claimed.

Tether says Devasini sold PAG in 2008 and was not involved with the company after that point, before clarifying that he began winding up the business in late 2009.

Tradeloop’s forums in 2010 include emails showing Devasini dealing with the complaint, and messages from an associate saying Devasini had personally packed the boxes.

At the time, Devasini strongly denied the buyer’s claims, said the packages must have been tampered with en route and offered partial compensation.

“This was a minor commercial dispute from more than 10 years ago, which has nothing to do with Tether or Bitfinex,” Tether says.

Combative crypto proponent

By the turn of the decade, Devasini, in his mid-40s and with much of his business empire in liquidation, appeared to be looking for a new project.

He had launched a shortlived food delivery service called Delitzia that included a blog about the benefits of organic food. In a November 2009 video posted online, Devasini, on his balcony in a loose-fitting white shirt and with a large garden gnome on the table, made nettle risotto.

Then in 2012, Devasini found bitcoin and threw himself into the crypto world which was, and still largely is, a wild west of unregulated finance. He joined Bitfinex soon after its founding that year, running its trading and risk management operations.

His early conversations with customers on Bitcointalk, a popular Bitcoin forum, showed him to be jovial with well-wishers and combative with critics. “I believe you should show some respect and gratitude for what we at Bitfinex are all doing for you,” he told one in 2013.

Tether followed in 2014, though until 2017 the full extent of the common ownership and management of the two companies was not widely understood. Devasini, along with the other executives at Bitfinex and Tether, own the companies personally and operate from different locations across the world. Devasini’s “merlinmagoo” Skype account currently gives the African island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe as his location, while corporate records list addresses in Switzerland, Italy and the French Riviera.

To outside observers, Devasini is an elusive character, declining to speak to the mainstream press and today maintaining a minimal online presence, a break from the archetype of the bombastic and defiant cryptocurrency entrepreneur. “It’s a matter of style,” says Stuart Hoegner, the companies’ Canada-based general counsel. Devasini is “just a little more retiring”.

But for Bitfinex and Tether’s customers, he is ever present.

“He’s responsive 24/7, and he’s not just responsive to crises or unbelievable opportunities, he’s responsive to day-to-day operations,” says Sam Bankman-Fried, the chief executive of FTX, a Hong-Kong based cryptocurrency exchange.

He says those day-to-day operations include processes like co-ordinating the purchase and redemption of Tether tokens for customers like himself with Deltec Bank, the Bahamas financial institution that is the bank of both Bitfinex and Tether.

Bankman-Fried says Devasini has “a lot of pride” in what he has built at Bitfinex and Tether. “He’s really grateful for the people that supported him. He’s certainly fairly annoyed at people he sees as . . . shitting on his businesses without real reason for it.”

Stable growth?

Despite the criticism and scrutiny it has received this year from US authorities, Tether has continued to grow dramatically in recent months — and become even more central to crypto markets.

In the first half of 2021, the company’s growth accelerated dramatically; 40bn new coins were minted by the end of June, more than the total issuance of its nearest rival USD Coin.

Bitfinex has also prospered. Although it is not the largest exchange, it is a key venue for large crypto-traders seeking liquidity and margin. “That’s where price discovery happens. It’s truly the institutional venue in crypto,” says one crypto company executive.

Today, just 3 per cent of Tether’s reserves are in cash, according to a breakdown the company released in May. Half, around $30bn, is in commercial paper, meaning short-term loans advanced to other companies, according to the disclosure.

A major source of the criticism from US authorities has related to disclosures about Tether’s reserves. Until February 2019, Tether said that it held a dollar in cash for every tether token in issuance. Subsequently it has said every token is backed by dollar assets.

However, the New York attorney-general’s investigation found that at times before the February 2019 disclosure, large amounts of Tether’s cash reserves were held in Bitfinex bank accounts. This “obscured the true risk investors faced”, the attorney-general’s office said.

For several months in 2017, Tether had no access to banking services and at one point more than 85 per cent of its cash was held in a Bitfinex bank account, accounted for as a “receivable” from its sister company, the attorney-general James found, with the remainder held in an account in the name of Hoegner, the general counsel.

Subsequently, in 2018, Tether lent Bitfinex $625m after the exchange suffered the loss of $850m that it held with a Panamanian payment processor called Crypto Capital Corp. Bitfinex has said a significant portion of the funds were seized by authorities and that it is trying to recover the money. In 2019, the US charged two people linked to CCC with bank fraud.

The loss did not become public until April 2019 when it was revealed in a court action brought by the attorney-general. Messages revealed by James’s office showed Devasini, under the alias “Merlin”, pleading for months with a CCC individual called “Oz” for the return of their cash.

“Please understand all this could be extremely dangerous for everybody, the entire crypto community. [Bitcoin] could tank to below 1k if we don’t act quickly,” he wrote in October 2018. At the time, it was around $6,500 per bitcoin, according to crypto market analysts CoinGecko.

Tether’s critics, including claimants in a US class action lawsuit, have pointed to this line to claim that the cryptocurrency has been used to pump up the price of bitcoin.

Hoegner, the Bitfinex and Tether general counsel, said it was “missing the point” to view that message as a price prediction, saying it was “born of frustration” and that Devasini had simply been trying to apply pressure to force CCC to “do the legal and right thing”. The company has described the lawsuit as “absurd and groundless”.

Bitfinex survived the crisis, helped in large part by drawing on the $625m from Tether in November 2018 and a fundraising in 2019. The Tether loan, subsequently formalised in a $900m credit line collateralised with shares in Bitfinex’s parent company, was unknown to the market until April 2019 and was at the heart of the attorney-general’s finding this year that Bitfinex and Tether had misrepresented the status of Tether’s reserves.

Tether and Bitfinex neither admitted nor denied the finding. Though the settlement came with a $18.5m fine, they say it has vindicated their position that Tether was always backed, even if at times its cash was held by Bitfinex.

“The loan was repaid in full [in January], with all interest due and ahead of schedule. So that was a good receivable all along, as we always have said it was,” says Hoegner.

The companies say the fine was “a measure of our desire to put this matter behind us and focus on our business”. Or, as Devasini’s WhatsApp profile picture puts it: “Life has no backspace.”

kadhim@ft.com / sid.venkataramakrishnan@ft.com